The Feminist Combining Process

created by:

Sangeeta Ahmed, Ashley Howard and Hiywete Solomon

Living Wage

A “living wage” is defined as a salary that allows a full-time worker to meet her basic needs, such as food, rent, and medical care. Currently, a full-time worker making the federal minimum wage of $5.15 per hour will earn $10,712 a year, putting her barely above the federal poverty threshold for a single adult. (19, 6) A married couple with two children working full time at minimum wage earns less than the federal poverty threshold for a family of four. Both of these situations characterize the so-called “working poor” in the U.S. The Living Wage movements seeks to increase the minimum wage, often through passing laws at a municipal level, to help with the achievement of economic justice.

Although poverty is not limited by gender, the Living Wage is a Feminist cause because women represent 61% of those at the minimum wage level, and over one third of minimum wage workers are working to support a family. (19) At the same time, the benefits of a living wage are not limited to women, making it not exclusively a Feminist Issue. Thus, the involvement of the Feminist movement in the Living Wage movement represents External Feminist Combining. Mainstream Feminist organizations such as NOW have taken on economic justice and a Living Wage as a platform, although the effort is still largely one driven by coalitions.

The inclusion of economic justice in the Feminist movement addresses the needs of working class women, a group not traditionally considered a priority. External Feminist Combining is demonstrated by the Living Wage movement through the building of coalitions, when Feminist groups work together with other organizations toward the same goal. In the struggle to increase minimum wages, Feminist groups have allied themselves with groups formed around workers’ rights, people of color, and religious activists, who see the need for a living wage as a moral imperative.

According to conventional economic theory, the structure of the labor market means that increasing the minimum wage results in fewer jobs for those at the bottom of the earnings heap, as employers attempt to make up for higher wages. Empirically, this has not been the case. Studies of areas with living wage ordinances have shown no drastic changes in the labor market in the form of mass layoffs or business closings. Generally, it seems the savings firms incur from lower employee turnover due to increased loyalty make up for the increase in wages. (Economic Policy Institute)

The Living wage movement began in Baltimore in 1994 with the passage of a municipal living wage law that required all firms with city contracts to pay workers a living wage. Subsequent local efforts have modeled themselves on the Baltimore campaign, attempting to pass local ordinances that mandate firms above a certain size that have contracts with the city pay a certain wage. Very small firms and non-profits are often exempted. Other efforts have worked to mandate a higher minimum wage for all employers within a city, in both public and private companies. The small-scale campaigns for local wages have paid off; there have been 140 successful ordinances across the country.

(1)

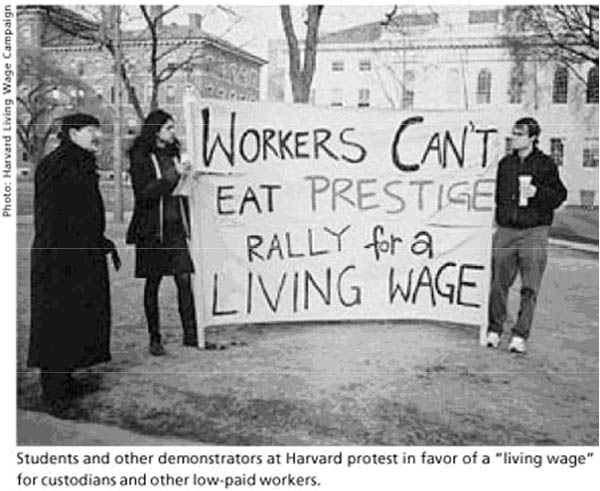

Another branch of the Living Wage movement is occurring on university campuses, as students Combine with low-paid staff members, again, frequently women of color, to pressure the school to pay a living wage. The effort at Harvard cumulated in a dramatic sit in, and resulted in an increase in the base wages for the university’s janitors, dining hall workers, and other low-paid staff members. (9)

Copyright Harvard Living Wage Campaign